This essay was published in Entropy Magazine in 2021. Entropy ceased publication in 2022, so it is republished here.

My aunt and my mother finally stopped speaking to each other on an early-autumn morning in March ten years ago when my aunt met my parents off a six a.m. flight from Los Angeles, thrust ten thousand of my grandmother’s dollars into my mother’s hand and told her they were never welcome in her home again. Expecting to receive a phone call from within the warmth of the house in the Titigrangi hills, instead I opened an email from my mother, reading it in confused silence on my phone in the dark of a late-winter London morning. She explained the encounter that left them alone in the arrivals hall of Auckland International Airport after a decade abroad. My aunt hadn’t specified what they’d done to be excommunicated, but ever-practical, Mum got down to logistics.

… so right now we have a rental car, and are staying in a motel called Lincoln Court Motel, unit 7.

We’ve found an internet cafe just along the road which is where we are right now.

Apart from that, the journey from LA to Auckland was good. We were even treated to a glass of champagne by one of the crew as he was so happy for us to be arriving back in NZ.

Possibly talk to you later on.

Love, Mum

Fifty metres down the little lane in which I’d made my home when I moved to the UK, London’s Smithfield Market was in full flight at dawn, butchers stained red from starched lapels to white wellies; stout shouts and slammed van doors providing the melody of the morning. But the ringing in my ears invoked the confused, silent terror of good news gone horribly wrong, confusion, happy endings shattered. This was not in the script.

I’d long harboured fantasies of what coming home would look like for all of us. My parents and I had been immigrants and emigrants for almost half my life. The journey to New Zealand is a lengthy one from almost everywhere on earth, more than enough time to let fatigue and pinot noir stir sentimentality into a furor. I had imagined my parents buckled in for the final descent, homeward bound after almost a decade in the hot yellow and green alien worlds of Florida and the Caribbean. In my mind, the sea and smattering of light clouds would appear from the soft morning gloom an hour before landing. Grease from sweaty foreheads and condensation from noses would cloud the window as they pressed their faces against the plastic, eyes playing tricks as low clouds morphed into dawn coastline. Bays and hills reveal themselves in the soft light until the shock of Auckland urban sprawl begins, then the inland water, and the plane sweeps over the Manukau Harbour with the airport on its abrupt eastern peninsula. I wasn’t promised this. I made it up.

I looked up the Lincoln Court Motel. One star. Every website. Grim as fuck. No stars, if the review site allowed. Photos taken under a mottled March sky. Cracked porcelain, broken furniture, dirty bathrooms, as if a stained and sagging mattress could metastasise into an entire business. A couple of suitcases and two black passports. No phones. No car. No internet. No family. Ten thousand dollars. A glass of champagne from the air crew on account of returning home. Nau mai. Welcome.

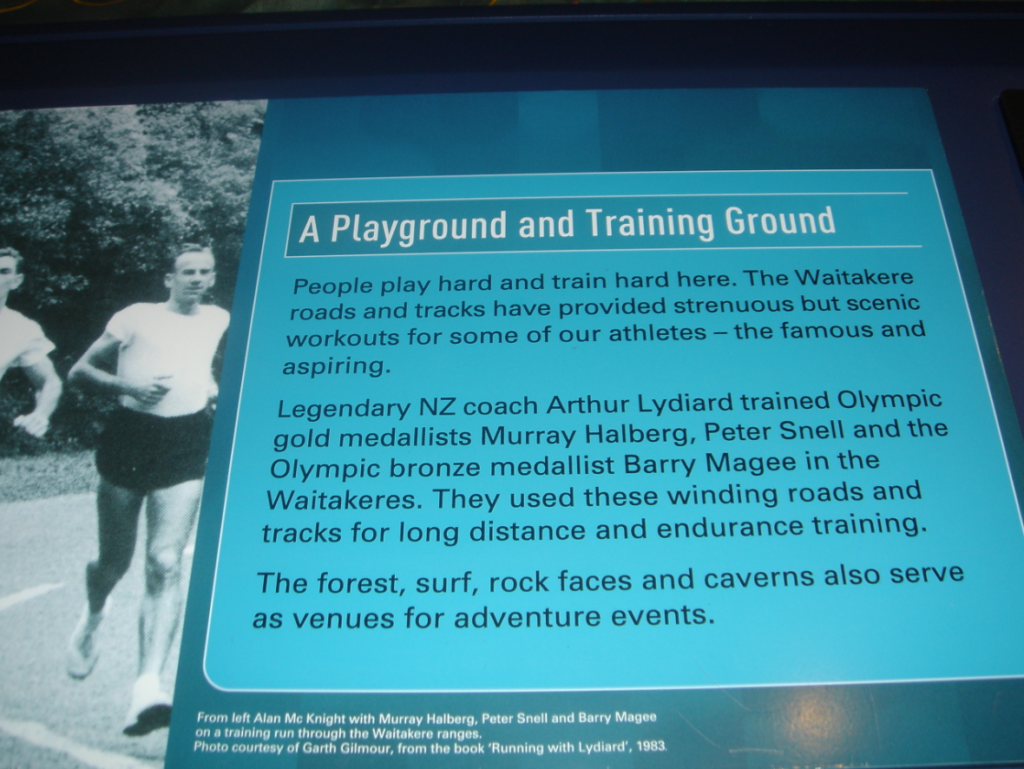

We do this. If you aren’t from New Zealand, you don’t know how this works. We demand homecomings; we demand good news. We revel in a failure. And then we punish all three, desperate to see and beat the world, and then woefully uneasy with the results. And maybe that, as opposed to only musings about compassion and strength, is the ironic side of how New Zealand faced 2020 with conviction and earned an odd place with its head above the parapet: an international “tall poppy.” A country known for exalting and then cutting down its home-grown tall poppies, insatiably keen to see its sons and daughters at the top of international stages, New Zealand is equally keen to take a swipe before the landing gear has descended above Manukau Harbour and the wings have turned into the bracing westerly hurling salt water into our faces from the Tasman Sea. They’ll clip your wings, when you get home, a line from a New Zealand novel, a book that shaped me more than I’ll probably ever know. We crave recognition more than any other nation I know of. We love to travel. We deify sportspeople to an unhealthy degree, grabbing hungrily at the shoelaces of our runners and rugby players, idolising musicians and actors, praying that someone peers over the equator and scans the vast emptiness of the South Pacific and says, I saw that, I see you. And when they come home, win lose or draw, we clip their wings.

I want to go home.

It was the winter of 1999, ten years before my parents’ fraught repatriation, and several of my friends were heavily invested in a project to ingratiate themselves to the filmmakers whose principal photography was about to begin on a series of fantasy movies in and around the city of Wellington. I had never read a fantasy novel in my life and my knowledge of films in the genre began and ended with Labyrinth. One friend in particular, two years older than me and on the hunt for something to do after high school, was particularly keen. It was, he said, going to be big. Put us on the map. So much more than rugby or yachting or bungee jumping: these films were going to change everything. I neither fervently believed nor disbelieved him, the film industry so far out of my area of interest that I both took his word for it and forgot about the conversation immediately. I was only reminded of him again while sitting in the drive-thru queue at the Jack In The Box burger restaurant in Spokane, Washington four years later when the girl handling my BNZ credit card asked, ‘Where’s New Zealand at?’ and her colleague replied, ‘Isn’t that like where they did Lord Of The Rings?’

Prior to this, many years and many international trips had gone by where I’d met people completely unaware of New Zealand’s existence. My time abroad had been exclusively for competitive swimming (I was in my late-twenties before I ever went on a trip overseas that wasn’t to work or compete) and more than once, I met people who hadn’t heard of us, or if they had, had no idea where the country was. Even into the late-nineties and early part of the twenty-first century, we simply did not register for a lot of people. We had never done anything noteworthy enough.

We started with films.

“The lady PM dreams of jabbing everyone by force and perma-prison for those who refuse?” It’s 2020, and it pops into a conversation with an industry friend about immigration and homesickness like so much wadded, stale bubblegum. “Nice place, no wonder people leave.”

“Seems a bit authoritarian down there. Aren’t they all still in lockdown?” Another friend, all information gleaned from YouTube, months after my parents had started going back to their, and my, favourite restaurant every Thursday night.

“New Zealand now has a fascist government under @jacindaardern. Are you going to act, @amnesty?” Former Deputy Chair of UKIP, Suzanne Evans, October 2020.

“While President Trump was labeled a “fascist” for suggesting the election should be delayed due to coronavirus, New Zealand’s Prime Minister just did exactly that with barely a whimper of dissent.” American political commentator, Paul Joseph Watson, August 2020. Ardern’s party won the election by a historic landslide two months later.

“New Zealand is a disaster in the making.” American journalist, Jordan Schachtel, August 2020

“New Zealand I would just get fed up and isolated, it’s not the utopia people make it out to be.” A former friend, whose knowledge of my country appeared minimal enough to be nonexistent when we were close.

“The places they were using to hold up now they’re having a big surge… Big surge in New Zealand, you know it’s terrible.” American President, Donald Trump, August 2020, as New Zealand recorded twenty-two new cases of the novel coronavirus in two days, to the United States’ 80,756 over the same two day period.

“Jacinda Ardern is a fascist. Change my mind.” – The chorus according to Twitter, 2020.

They say life comes at you fast, but for us it was a slower burn. I am locked in my home in England, unable to turn a screen to my face without seeing opinions about my country. Twenty-one years is a long time. I harked back to the drive-thru queue, Red Bull and curly fries marinating between the scratchy synthetic seats. Where’s New Zealand at? From the starting position of barely existing, it was abruptly clear that our time as a backwater, an afterthought, a dot of irrelevance at the bottom of the world was over.

Both the nation and its leader had gained global attention one year earlier when a terrorist opened fire in two Christchurch mosques: Ardern received immediate respect for her compassion towards survivors, victims’ families and the community, as well as notoriety for her government’s subsequent ban on semi-automatic firearms. But a year later, the country was faced with the same problem as every other nation, and rather than having the world watch on while one country dealt with an isolated incident, New Zealand’s response to a crisis was compared to everyone else’s. We started with films, and then there was wine, and there were singers and earthquakes and tourism and actually winning the Rugby World Cup for once, and TV shows that everyone quotes at you (“Murray, preesint”), and a fatal volcanic eruption just weeks before New Year’s Eve, 2019. And then there was COVID.

This is not to say that New Zealand has not made political waves before. In the late-1980s, the country outlawed nuclear powered ships and weapons, effectively making the nation and its waters a nuclear-free zone. This was a wildly popular policy with the New Zealand public, who had protested visits by United States vessels in the past and who were incensed by the 1985 French state-sponsored bombing of a Greenpeace boat in the Port of Auckland whose activism included protesting French nuclear testing in the South Pacific. Our anti-nukes stance went down poorly with much larger, nuclear-powered nations, but as it took place about fifteen years before the widespread availability of the internet, we were not beset with the barrage of relentless opinion about our decisions. And further, we weren’t subjected to opinions held by people who didn’t know us and who assumed we hold the same values and exhibit the same cultures as they do.

March 2020, ten years after my parents arrived home to find themselves excommunicated from my aunt and her immediate family, and New Zealand’s borders slammed shut to all but returning citizens and permanent residents. Still in the UK, my husband and I slammed our own front door too, briefly considering a run for Heathrow with our son but deciding to lock down instead. During those terrible early days, I watched in horror as Ardern announced the measures New Zealand would take to control and, hopefully, eradicate the virus within its borders. Horror, not because I disagreed with her decisions. Horror, because I knew those were the only correct decisions a leader could make. Horror, because on the twelfth of March, I watched the UK’s prime minister and top advisors give roughly the opposite press conference. They were pledging, amongst not much else, to do nothing.

The UK continued to dither as case numbers and deaths rose. New Zealand went into full lockdown long before they reached population-comparable standards of chaos: the entire country came to a standstill for a month from the end of March. After two and a half months, the country reported no active cases of COVID-19 and lifted all restrictions but for its closed border. Subsequent minor “outbreaks” were met with two short periods of heightened restrictions in the Auckland area, and an extensive test and trace programme to bring them to a quick halt. My parents worked from home, then went back to work, went back to their favourite restaurants and pubs and even took part in a week-long court hearing in central Auckland. They complained about the traffic and got coffee downstairs and even received a hug from opposing counsel. Meanwhile, in England in October, I was on the same tank of petrol I’d bought in February.

‘You must be very proud,’ my neighbour Kevin said to me, standing on top of his roof. There was nothing to do. No school, no work. A carpenter, Kevin had taken to DIY around the house on account of projects drying up and supplies being too hard to find. We had bought a football goal and anchored it under the blossoming cherry tree. My five year old son had learned too many swear words already in the first horrible weeks of lockdown. We played a lot of football, showing off to Kevin as the only spectator.

‘That Ardern, she’s just amazing,’ he continued, as I prayed my son wouldn’t repeat whatever it was I’d last said in front of a Boris Johnson presser. ‘I wish we had her here.’

And I was, so very very proud, and very relieved that my seventy year old parents, whose health had taken a hit in the pay-as-you-ail system of the United States, were back home in a nation that was looking out for them in more ways than one. That same week in April, the FT published an article whose title I will never forget, “Arise Saint Jacinda, A Leader For Our Troubled Times”: a piece whose honesty about both her great leadership in times of crisis and the 2017 election promises her government were yet to fulfil managed both balance and exaltation. But with exaltation comes so much more: expectation, envy, skepticism, intense scrutiny. I was proud as punch, telling Kevin that I couldn’t wait to vote for her in the general election later in the year.

Kevin didn’t ask, that afternoon with him on his roof and us running laps of our garden, but it was the question on everyone else’s fingertips: will you guys go back? And while we’d made our peace with no, we won’t–not yet–another stressor was looming, both online and between family members. As citizens, around one million of us abroad were still permitted to enter the country on the condition that we isolated for two weeks, first on our own reconnaissance and later in hotels managed by the government. But a growing, vocal sentiment was making itself known: We don’t want you to come back. “You are not welcome in this house.” Do not come home.

It pops into my timeline because of how many of the people I follow have liked it.

“Dear returning Kiwis. IF you haven’t bothered getting yr lazy butts back to NZ by now. Don’t bother coming home. If you’ve come home – we’ve run out of tissues to keep wiping your arses with.”

A small but very passionate minority let us know how they felt. Close the borders. You had your chance. You abandoned us, thought you were too good, thought this, thought that. They presupposed everything about why we left and why we continued to live abroad, seeing only a monolith of the othered: one million unique people, lumped together as out-of-luck traitors. They also seemed to assume that throwing together a bag of essentials and making a run for the airport was within everyone’s means, and that flights were not being cancelled and re-cancelled endlessly for those who did, or that many of us have mixed-citizenship families who require extra time and clearance to enter New Zealand at present. If you have never made a big geographical move, let alone an international one, maybe you don’t fully grasp what a herculean task it can be, even for those with relatively little belongings or responsibilities. When I left the United States for London in my mid-twenties, I did so with only two suitcases, no family, no pets and no kids, and it still took me a month with no pandemic to hold me back. Be kind had done the social media rounds mere months before these sentiments hit. My brain couldn’t piece together the first steps of moving us, right then, like this. We remained, but we still saw all those messages; digital renderings of my aunt pirouetting out of the arrivals hall.

A lot of the arguments about why New Zealanders shouldn’t be allowed back centred around the cost of government managed isolation and whether this cost should be covered by the government or charged to the returnee. And for the economic argument, I felt guilt and understanding. I had spent eighteen of my thirty-six years outside of New Zealand. I left when I was offered a full athletic scholarship in the United States, finding employment and eventually marriage and a family in the years afterwards. It was life, and it happened. I did not want to ever rip my country off. We would be able to afford a fee if one were charged for our quarantine. But I also found unease with the notion that a price could be put on the benefits of citizenship, namely for those people who can’t afford it or have no safe alternative than to go home. And while I believe the solution the government came to is largely fair (returnees pay three thousand dollars for their quarantine if they left New Zealand after the pandemic began, i.e. “You knew”), it was clear by this point that some would prefer we were not allowed to return at all.

I was reassured by friends that these views were indeed a minority, but I couldn’t help but think of my parents emerging from the wide gates of International Arrivals and facing sudden, unexpected hostility. And like my aunt who refused to articulate exactly what we had done to earn her wrath, it was clear that money was not the only factor in the hostility facing returning New Zealanders. For many, it was simply the safest and most tangible to express on Facebook. We were being punished for a transgression much older than COVID, much older than Ardern’s government, much older than Ardern and I alike. We were being punished for having left in the first place.

Some New Zealanders’ fraught relationships with their compatriots don’t end with unease at international success. The unease extends to prolonged international travel itself, regardless of what you did with your time or if you did it well. An air of resentment has long been leveled at those who’ve made lives abroad. There is also a strong denial that this phenomenon exists. But it’s a very understandable feeling, even when it’s being pointed at you. In short, it is likely that New Zealand spent so many years tolerating the first girl on the registers at Jack In The Box–where’s New Zealand at?–that resentment and indignation warped some people’s perspectives on citizens who’ve chosen to go abroad, as if we also thought that the country was irrelevant. It is the need to say, hey, don’t belittle me like that.

I had experienced that insulted indignation myself, on account of my American college boyfriend and now ex-husband of a decade, who pestered me several times during our marriage about “making sure to get my American citizenship.” He incorrectly believed that I would have to give up my New Zealand citizenship to do so. He also firmly believed that being American was “worth” a lot more than being a New Zealander and had no particular interest in visiting, harbouring the “backwater afterthought” sentiment to which Kiwis are very sensitive. We knew we had value before the films and the wine and the ads and the progressive young female leaders. We knew we had cultural uniqueness and that we shouldn’t be consistently left off world maps, assumed to be on the hunt for other citizenships to replace our own, or equated with nothing more than colonial suffering and sheep. And so when COVID hit and New Zealand’s swift, self-assured and effective response left it as one of the most functional societies on earth, some of us decided to take the collision of that ingrained frustration and sudden success out on each other.

… it’s not the utopia people make it out to be…

Being forced into an international spotlight is rarely an experience free from contradiction and confusion. I stood in my kitchen and looked at those words, tweeted by a former friend who had briefly joined the New Zealand-bashing bandwagon. And I thought to myself, how can you be cross with that statement when it’s true? The picture of a progressive, trouble-free paradise was far from complete, no matter how deep my love for it ran and how desperately proud I continued to be with its efforts and successes, and how proud I had always been to be a New Zealander. People impressed with New Zealand’s response idealised the nation’s population and its leaders with blind praise. Sainthood was bestowed on the PM by a leading London newspaper. The picture of my country painted for me by well-meaning friends in the US and UK was one of beauty, care, courage, understanding and universal good-will. And while I knew a lot of that existed, I also knew the perspective lacked nuance.

It knew nothing of the damp, leaky houses that plague the country. It knew nothing of the ongoing child poverty. It knew nothing of racism. It knew nothing of classism, domestic violence, inequality. If it did know about any of those things, it didn’t know what forms they take in a unique environment that isn’t a little Britain or a little United States, or even a little Australia. People idealising New Zealand didn’t know that I’d recently blocked two cousins on Facebook for meanly implying that I shouldn’t be allowed to come home and that I was selfish and greedy for wanting to come back. And the people decrying New Zealand didn’t either. For those of us who sat through so many conversations with people who didn’t know we existed some twenty years earlier, it grated. Everyone’s an expert now. It’s not the utopia people make it out to be.

Of course it isn’t. But it showed excellence. The former afterthought showed strength and forethought. Just as it had turned away nukes in the eighties and semi-automatic weapons in 2019, it made a series of difficult decisions and it made those decisions to save the lives of its people, not for the sake of adulation, domestic or international. The government received plenty of criticism at home for some of its measures, but they largely prevailed in achieving and maintaining their goals: eradicate COVID-19 in New Zealand, or keep a very tight control of it when it was found to have snuck in. There was no point in reductive musing on whether or not New Zealand is a utopia because such things don’t exist. It is complex, unique, flawed, brilliant.

I realised I was insulted and defensive when I read foreign critiques, not because I thought the country was perfect, but because they were simplistic and uninformed, and often from people who’d never spared us a thought before. The country itself was now a tall poppy, and social media had done what it always does, giving people a limited space to air their complex emotions, jealousies, insecurities and fears. Disaster in the making, fascist, isolated: at least they knew where we were now (highlighted by how many were keen to downplay New Zealand’s success as being due to its isolation, rather than geographic position being just one important tool at the government’s disposal). But their opinions displayed little more complexity than the second teller at Jack In The Box, correctly identifying the filming location of Lord Of The Rings.

When you come into land at Auckland on an international flight, it’s usually early morning. From their home in West Auckland, half a mile from the Lincoln Court Motel, my parents can hear the jets at five, six, seven o’clock. In the height of the pandemic’s first wave, there were very few, the silence in the sky mirroring that on the ground. On account of the border restrictions, the only passengers were Kiwis or their families, and when she heard them early in the morning, my mother told me how much she liked the low roar of a 777 coming into land. You’re back. Welcome home.

The last time I flew into Auckland was my mother’s birthday in late 2019. While we didn’t know what was about to befall the world, we’re always aware of the vast distance we have to travel to get there, and how even if it’s “only two flights”, they are some of the longest flights anyone can take. Despite it being summertime and just after dawn, fog and low cloud hid the bays and city alike until we were right over the harbour. I understand simplistic emotion; in those moments there is nothing but excitement and gratitude. There’s no complexity or shades of grey. Long before COVID, I imagined being on that plane over and over again. If there is a contradiction between someone finding that their choices have led to a life abroad, and an insatiable desire to come home, I don’t mind owning it. There was never a government or a population or a family or a person free of contradiction, hypocrisy, confusion, fear. There are no saints. There are no utopias.

They’ll just leave again. If you take us back, the wanderlust may sink but it will forever simmer like the cauldrons at the heart of our mountains. Our last great contradiction is how many of us keep that eye on the sky no matter how often we’ve wished we were home. They’ll come for their holiday until COVID is over and then they’ll be gone. But would I, if it were me? And if they do, whoever they are, does it matter? As frozen fog sinks around my house in England the day after American Thanksgiving, a house I have barely left since February, I know as much about how I’ll emerge from my personal tussle with being a Kiwi abroad as I do about anyone else’s. If only it were easier to admit how many things you don’t know, even about yourself. That simplicity, the black-and-white thinking, the monolith: I stopped replying to it, stopped sharing posts and tweets that refuted it. I tried to stop being angry at those wide-handed swipes of generalisation, so readily slapped across our uncertain faces. I have tried to become more comfortable with uncertainty and contradiction. I have tried to understand that when the script calls for fog that reaches the ground, at some point the sun will shine on the other side of the arrival gates.