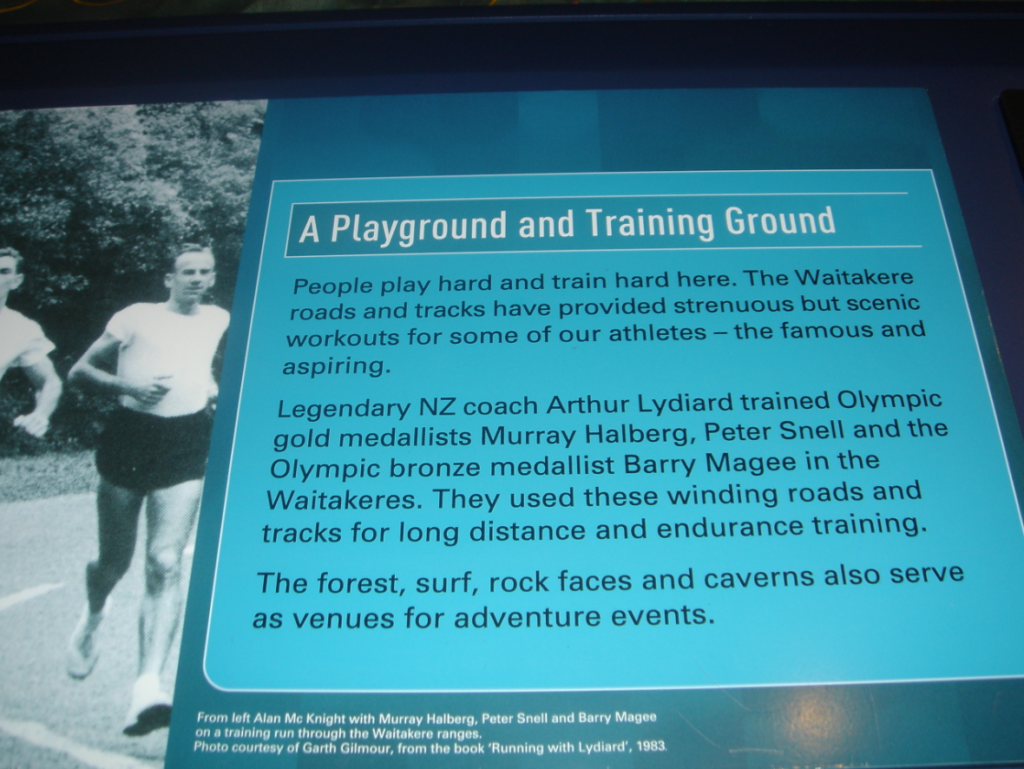

In the haze that rises off Manukau Harbour, the hills stretching beyond West Auckland are known for little but their leafy suburbs and relative inaccessibility from the city by public transport. After homes at the end of Titirangi’s evergreen crescents give way to bush, Auckland’s city limits are thought to come to an end, but once the sharp, clean asphalt has surrendered to trails, there begins a trek through the ranges that has become synonymous with a coming-of-age of runners. A handful of people began pounding out this route through Auckland’s volcanic hills in the 1950s because a burgeoning coach called Arthur Lydiard told them to.

People like Arthur shouldn’t usually be trusted. Normally, you’d be advised to steer clear of someone as zealous as this man, a young man in the late 1950s, who had some brilliant ideas that were completely at odds to the common practices in New Zealand athletics training. In the 1950s, Arthur’s idea that runners should complete one-hundred miles per week of endurance running for ten weeks before embarking on speed work was unproven and virtually untested but the sharp-tongued, gruff Lydiard managed to convince a small number of people that he was right. Not often are someone’s initial guinea pigs the most successful athletes in a nation’s history.

Short, wiry, seemingly ever-weathered and grumpy if he didn’t think infinite justice was being served to the creed of running, Arthur’s utterance of “hello” felt like a lecture. The sparkling blue eyes at the top of a prominent Roman nose were visible from quite a distance and you always knew when you were being watched. Chances were, if he was watching you he was on your side. Arthur Lydiard did not waste his time on people who did not want to spend their time doing what he told them. He did not ask questions and he did not make suggestions: he told people things, instructed people as to what was fact and what was crap. You, he’d say, can be a champion. No reasons, unless you probed him. No explication. You can.

From the Arataki Visitors Centre, Waitakere, New Zealand, May 2008

There’s a period of certainty right before you embark on something like Arthur’s athletic regime. It is Sunday night and in front of you are ten weeks of training, mapped out for you by a man who claims he can take you to the Rome Olympics and have you win. You could have been down the track Monday morning, running eight-hundreds and practicing victory salutes but this coach who you’ve entrusted your career to is instructing you to hit the streets instead, pounding around the city of Auckland in the morning and again in the afternoon.

And on Tuesday, too, he says: just run. There is the certainty. It can’t be that hard to just run.

Six days later it isn’t hard anymore, it’s goddamned torture and you’ve yet to complete a tenth of an Arthur Lydiard training programme. This man, an unknown in the field of coaching, competed in the marathon at the 1950 British Empire Games for New Zealand but now he is telling you to leave the streets of Waitakere City, run through Titirangi and lose yourself in the bush behind civilisation, so far away from the Auckland Domain where your counterparts and milling around, waiting for their next time trial. And you don’t give up, return to town and find a coach who knows what a stopwatch is for?

View from the training ground: modern day Auckland City from deep in the Waitakere Ranges

As you disappear into the clouds onto some of the region’s most unforgiving hills and trails, hot and sticky in the summer, cold and sticky in the winter, the safety of the infield at a track, a passing motorist or a nearby payphone becomes as distant as the pavement. Aside from any training partners, people who have also been suckered into this deal and promised outstanding success, you are completely alone. Arthur Lydiard does not care if you crawl back into his house in the suburb of Mount Albert after you have completed your Sunday run around the Waitakere Ranges. He has promised you that in ten weeks’ time, you will be fit enough to run all the way to Italy. Sunday’s weekly journey around the Waitakeres was at once famous and infamous: hated and admired by those who laboured through it every seven days. In the ten years between Arthur’s participation in the 1950 Empire Games and the Rome Olympics of 1960, the people who ran that course would include future Olympic Champions.

Arthur Lydiard was born in 1917, and he died on a December afternoon in 2004 after going running in the morning. His critics will tell you that it was his training that killed him: all that distance can’t be good for the heart, after all. Sometimes it seems that people were waiting a good forty years for him to kick the bucket just so they could blame his ideas on physiology. A man who avidly practiced what he preached, Arthur’s idea was for athletes to ultimately achieve supreme fitness by running extreme distances. If being supremely fit means that one dies at the age of eighty-seven, then maybe that’s just the price you have to pay.

Long periods of aerobic running (that is, running at a pace that can be sustained without a person going into oxygen debt and having to stop) aren’t all that much fun. Neither are long periods of aerobic swimming, kayaking, or cycling and to top off the fun, an “aerobic” pace is by no means “slow”. There is an intensity involved in completing an Arthur Lydiard-style programme that will wear a person’s body down to their last shreds of fat, sometimes producing athletes who look like they would be better off in hospital, or at least at Burger King, than out running.

All that messing around in the bush behind Auckland definitely prepared one athlete rather well for his Olympic event. Barry Magee competed in the marathon at Rome, a race whose passage up the Appian Way took runners over ancient rocks, in the dark, with the flashbulbs of photographers going off in their faces.

Magee first came to believe that Lydiard was onto something decent when he was eighteen, eight years before Rome, and “all the boys in Arthur’s stable were improving faster than anybody in the country.” Magee saw himself and others progress quickly from day one. Up and down New Zealand, Arthur’s name was gaining infamy but true to human nature’s stubborn form, nobody outside of his small circle was listening.

“In (my) first year, there was one Auckland coach who was emphatic that Lydiard’s training would kill me and others. He said this to my face so I know it’s true,” says Barry Magee. This is a notion that is hinted at often by the non-believers, the critics and the doubters, of which there are plenty. You will end up in a wheelchair. You will be plagued by heart problems. No human body can stand that kind of work. You will lose your speed and never get it back. To the last assertion, Arthur’s response was always, where exactly would said speed go?

“I did not have many others tell me directly that his training would not be successful as the results we produced soon squashed the critics, but I did hear of the murmurings around New Zealand that Lydiard’s training would put us on the scrap heap and we would all burn out by the volume,” Magee continues. “Most of it came simply through professional jealousy. We all either ignored it or said, “watch our backs!” or something similar, as we demolished the rest of New Zealand.”

Both of the warnings Magee heard never bore fruit as many of Arthur’s first athletes are still alive or lived long lives, and many had very long, successful careers, not “burning out” at all. But despite this, through the fifties, the sixties, seventies, eighties and nineties, followers of Lydiard’s programme have been threatened with death, illness and other equally unlikely side effects. Exploring why it is that people just won’t convert to Arthur’s way is an extensive exercise in itself.

The reason his programme, with its emphasis on aerobic activity, is relatively unpopular seems to stem from three sources. Firstly, it’s boring. Oh hell, it’s boring. It’s endless and relentless and the moment an athlete finishes a workout, she knows that she has little time before she’ll be up and running again. No day of the week was spared for rest.

“If you have a day off every week, that’s fifty-two days a year,” Arthur barked on many an occasion. “That’s a month and a half. How are you going to beat someone who’s trained for a month and a half more than you have?”

The second reason is that it isn’t rocket science. Somehow Arthur’s plan seems too simple to be true. You run a long way. Then you spend some time back at the athletic track, running fast. Then you win races.

Across all sports, many coaches and athletes can’t handle the idea that it’s this easy and this hard at the same time. They want to find a scientific formula that will make the process seem more complicated and will cut out the gruelling work. Tables and charts and monitors and tests, wires attached to every limb and tubes shoved in every orifice makes athletes feel like a mathematician and a doctor will feed their statistics into a computer and print out a ticket to success, where the backside of West Auckland will only be seen on a flight to the World Champs.

Thirdly, results are slow to be seen during the hard, hard training. Out in the bush behind Auckland, athletes can time how long it takes them to get back to town, aching and miserable, but imagine the disappointment and demoralisation when Week Four’s run took ten minutes longer than Week Two’s! Arthur will have explained that sometimes your body will be slower than before and that the training is still working, but shit. How do you look him in the eye and tell him you still believe?

And be prepared: if you don’t believe, you won’t be required to pretend for very long. Famously, Arthur never took back a runner who had left him for another coach and subsequently changed their mind. The most striking example of this was Nyla Carroll who held the New Zealand record for the half-marathon at 1 hour, 10 minutes and 53 seconds from 1996 until 2011. After leaving Arthur’s coaching regime for that of former New Zealand running great Dick Quax, Arthur virtually ceased to care whether or not Carroll existed, cutting her dead and refusing to take her back when she changed her mind about Quax.

“There were no shades of grey with Arthur,” says New Zealand swim coach David Wright, who also coached runners during the seventies and eighties, using Lydiard principles. “He was your very best friend and would die for you, or you didn’t exist. Your dedication and your faith determined how you were treated.”

Wright was also responsible for much of the work that went into converting Lydiard training from running to swimming, spending almost ten years perfecting a regime in the pool. He has published three books on the subject, Swim to the Top, Swimming: Training Program and Shaping Successful Junior Swimmers. As orthodox as they come in terms of Arthur’s believers, Wright made sure to adhere to the doctrines initially set forth in the 1960s.

“The job I had was to use what I knew about swimming to adapt his principles for the pool, but not to change them one bit. To change them would be virtually sacrilegious.”

Sacrilege. Unorthodox. Believers. Passionate people use words like these. They hint at an element of obsession. One could wonder why Arthur Lydiard cared so much about what he did. A man who died on tour in Texas coaching Houston’s offering of athletes, something drove him to distraction about both his principles and those who believed in them. Renowned teacher, writer and runner Roger Robinson thinks that Arthur’s fixation with athletics stemmed from a few places. First and foremost, his obsession was personal.

“(His programme) wasn’t just a scheme,” Robinson says from his home in New York City. “It was not just a teacher teaching chemistry; he was teaching something that he had invented. It was highly personal.”

Robinson, who lived in New Zealand for many years, knew Arthur well. Amongst Robinson’s achievements in sport was a victory in the Master’s section of the New York Marathon. He sees Arthur’s personality as being highly fueled by personal interaction, and he had respect only for people who showed him their worth through actions, rather than words.

“I wrote to him after the death of his (second) wife, Eira,” Robinson continues. He is talking about how he and Arthur first became friends. He had met Arthur and Eira at a function only six months before she died of cancer. “I told him that I felt bad for him. Arthur never forgot that. The personal contact. From then onwards, we were friends.”

And why shouldn’t a man like Arthur take things personally? He’d fought a personal battle to gain what he had. Having never attended university, in the days before earning Olympic success his work as a coach was supplemented with employment in a shoe factory and as a milkman. Part of his motivation seemed to be the desire for people to be like him: willing to work really, really hard. After a day’s work in the factory or delivering milk, Arthur would come home, drink some tea, and go for a run. Why the hell couldn’t everyone be that dedicated?

“What frustrated him the most was when people didn’t work,” Robinson says. “He realised that hard work had made him successful. He felt betrayed when people expressed an interest and then didn’t work. Why am I wasting my time?”

This sentiment is echoed by Magee in a tribute he wrote about Arthur on runningtimes.com. Six other tributes appear on the site, written by some of athletics’ more influential people. Magee recounts the first time he met Arthur. His coach Gil Edwards had decided that Magee was too talented for Edwards but that Arthur could do Magee justice.

“Son, are you prepared to run 100 miles per week? If not, just tell me, because you would be wasting your time and mine,” Arthur said. Having “stuttered out the word yes,” Magee found himself in Arthur’s care for another twelve years.

The refusal to be shortchanged by anyone, whether it be by someone’s criticism (which he took extremely badly) or by their lack of dedication, could often come across as qualities bordering on stubbornness and an opinionated vanity. However, those who knew him recognised that what was really present was, in Roger Robinson’s words, a complete conviction in himself. He was a “compulsive teacher” whose passion in life was helping others. Incidentally, he used the word “coach”very rarely. He referred to himself as a “teacher” and claimed to have “helped” people with their athletic careers.

“I helped the Finnish national team,” Arthur would say, referring to his time in Finland as a national coach. He’d say the same thing about being in Mexico and when referring to various other places he’d visited and runners he’d known. From his words, you’d have thought he’d just sent these teams and people a few letters, watched them run a couple of miles and gone home. In some ways, his programme was all about him – he invented it, he fought for it and he believed in it fervently. On the other hand, once his own running career was over, it was not about him in the slightest. When I was in his home, it was all about me.

Arthur Lydiard and me, Beachlands, Auckland, January 1999

People of my age and even those slightly older won’t recognise how pioneering Arthur’s attitude towards women athletes was. Women and men who grew up in the eighties and nineties have spent their entire lives understanding the notion of gender equality in sports. Of course to a certain extent, hangovers from the days when women were not considered fit to partake in heavy exercise still exist; however, in the time when Arthur was developing his initial programme the idea of anyone, let alone a woman, exercising as tirelessly as Arthur proposed was truly revolutionary. Arthur was an avid feminist in his refusal to entertain the thought that women couldn’t take part in his training.

Someone who should know about sexism in sport is Kathrine Switzer. She was, after all, the first woman to officially enter and run the Boston Marathon. Her 1967 entry of “K.V. Switzer” was assumed to be male. Switzer survived race co-director Jock Semple’s attempt to forcibly remove her from the event by leaping from a press bus and grabbing her. With her coach and boyfriend, Switzer finished the race in around four hours and twenty minutes, even though her time was never officially recorded and her participation not made official either.

Her experience in Boston and in future races gave her the determination to work for equality in sport. Seven years after her first Boston Marathon, Switzer completed the same race in two hours, fifty-one minutes, smashing the three hour “barrier” and running the race officially, as women had been welcomed to the event in 1972. Her efforts in Boston and worldwide are remarkable. She is married to Roger Robinson and talks about Arthur Lydiard with huge admiration.

“He believed in women’s ability to succeed when most people didn’t. He thought there was no difference. It was just a matter of making them believe,” Switzer says. But his belief in women, she thinks, also stemmed from a more personal source.

“Another motivation was his sex appeal. He was a sexy guy. Charismatic. Vain. He loved women’s attention, but didn’t like silly women. There were sunbeams bouncing off him! He was quick and critical and witty. Because of his personal belief in his success, he radiated a kind of aura. Arthur really knew that he was charismatic and he loved the attention that this brought him. He was motivated by his own charisma.”

Robinson and Switzer also point out Arthur’s egalitarian qualities when it came to runners. Not only did he take people to international glory, he also made people get out of bed after heart attacks and do some exercise. His knowledge of the human body and its physiology led him to believe that exercising after an illness is often the best way to a speedy recovery. Now, Nike does a roaring trade and “joggers” are prolific worldwide. Also laying claim to the coinage of the term “jogging,” Arthur wrote the first book on the subject, Run For Your Life. The single person who sparked this trend that now has everybody from high school students to pensioners pattering around the sidewalks, a half hour in Italy in 1960 is most certainly not the defining moment of Arthur Lydiard’s life.

Before I met Arthur personally, I knew him more commonly as God. This nickname was given to him by my mother, Alison, who was a middle distance runner in New Zealand and trained under a regime that mirrored Lydiard’s in many ways. She recognised his deity-like presence: the authoritarian air he carried with him, which often alienated those who did not know him.

My swimming career was what brought my mother into direct contact with Arthur as he was very much my mentor, but she remembers the first time he spoke to her well. It was 1977 and she had just won the New Zealand 1500 meter championship on the track. Her experience is telling of Arthur’s legend.

“I was walking along behind the grandstand and he was walking in the other direction and he said ‘hello’ to me. I was blown away because I didn’t think he knew me and he was Arthur Lydiard!”

She was rightly impressed. Arthur did not acknowledge people unless he thought them to have a touch of class, an obvious work-ethic and drive.

Alison Wright, Windsor Great Park, 1978

“I just thought (he had) done a fantastic job of changing athletics throughout the world. Although he didn’t coach me, it were his principles that were followed with any minor modifications that Arch made along the way,” Alison says, when asked what she thought about Arthur. Her coach, Arch Jelley, was also responsible for the career of John Walker, who won gold for New Zealand in the 1500m at the Montréal Olympics. Alison held the New Zealand national record over 1,000m from 1979 until 2014.

Arch is now in his nineties. He certainly employed some of the same principles as Arthur and enjoyed some similar successes, however Arch’s view of Lydiard training appears to be more cautious than some of Lydiard’s most devoted disciples, such as David Wright.

“While I believe in Arthur’s main training principles, I do not subscribe to the idea that there is only one way to achieve sporting excellence in any given field,” Jelley says. The former principle of Sunnybrae Normal School on Auckland’s North Shore holds the belief that the ways he and Arthur coached have extensive room for improvement.

“The coaches and physiologists in the more advanced sporting nations have taken Arthur’s ideas on board but have then grafted on their own ideas and philosophy to produce athletes whose achievements are far superior to those of Peter Snell and John Walker. I believe that training programmes should be regarded in a developmental way. That is to say, the ideal programme for any individual athlete has never been devised, but as greater scientific knowledge becomes available, training programmes change to take advantage of this new knowledge. Thus there will always be different approaches to what is the best way to train an athlete to reach his potential. Another way to say this is, ‘Many roads lead to Rome.’”

Until she met him and saw the way he cared about athletes who operated under his system, my mother assumed that this iconoclast, who inspired a religion of his own, was as cantankerous as his mannerisms would have you believe. What people who never encountered Arthur personally usually do not know about him is that he was an extraordinarily caring man who, as Wright said, would and did go out of his way for anyone who he felt merited his attention. He was blind to age, past achievement and talent when it came to those whom he cared about, and he would put as much thought and effort into a thirteen year old as a thirty year old.

When Arthur died, many people whose names never appeared on world or national rankings, and many who never competed in a single race, could relate to the internationally accomplished athletes whom Arthur helped. He’d made such an immense impact on all of us who’d believed in him and followed his lead. There are tales from New Zealand to Finland of his dedication. In London, England, my experience is one among many.

The man who watched Peter Snell and Murray Halberg run from Mount Albert to Olympic gold also drove for four hours in 2001 at the age of eighty-three to watch me and my one teammate compete in the New Zealand Winter Swimming Championships. As he sat on the Rotorua Aquatic Centre’s temporary bleachers, the pundits of New Zealand swimming eyed him with caution. They knew that they were in the presence of an icon whose reputation and worth they’d helped refute over a period of years. They’d told me and my coach, David Wright, many times that the doctors and the mathematicians could do more for me than some argumentative old bugger from the sixties. Arthur watched me win the two-hundred metres breaststroke and then he drove back to Auckland. You can be a champion, he’d once said to me. And, thank God, I’d bought it.

* * *

Never officially retiring, Arthur’s last home was in Beachlands, a settlement southeast of Auckland. Despite its close proximity to the new, gaudy Formosa Country Club, Beachlands is no Palm Beach County. Its charm comes from the streets without sidewalks, properties that end in the ocean and complete lack of influence from the city to the north. Arthur had hundreds of people come to his home over the course of his coaching career: he seemed to view it as a common courtesy to invite people to eat or stay with him at any time.

Sitting in the log-cabin style house with coaches and athletes and instructing them in his stern choppy manner of his opinion on their careers, his speeches on training, fitness and dedication would be interspersed with constant offers of coffee, tea, biscuits, glasses of water, or anything else a guest to his home might want.

“Jane,” he would almost snap at me, midway through a lecture. “Jane. Have a banana. Have a glass of orange juice. In the fridge. Or maybe the cupboard. Jane. Have a glass of juice.”

And he would never be satisfied until a guest had accepted the offer of hospitality. Contrary to many coaching beliefs, his kitchen was full of candy and treats, although he would insist an athlete put honey in her coffee instead of regular sugar and I still do. He had honey specially shipped to him from the South Island. It was, he believed, the best honey in the country. Even regarding details as small as the quality of honey, Arthur passionately believed what he was saying and so you did too. In Barry Magee’s words, “when Arthur Lydiard told me I could win a race, I knew I could.”

The first time this affected me personally was in the way Arthur approached me when I was thirteen and needed to swim a freestyle race in Auckland. I had spent the weekend swimming the breaststroke races at the Auckland Age Group Championships but on the last day of competition, the breaststroke events having been completed, I had been entered in the one-hundred metres freestyle. In the morning preliminaries, I had qualified for the final in second place. The girl who had qualified first had swum two seconds faster than I had. My family and I were staying at Arthur’s Beachlands house, forty-five minutes east of the swimming pool. Arthur decided half way through the afternoon that he would come and see me swim in the evening. We had been in the car for two minutes, driving west, when Arthur turned to me in the back seat.

“Do you think you can win tonight?” he asked. I was hesitant. Of course, with Arthur Lydiard coming to see me I would have to look slick, but the girl ahead of me was two seconds faster, a virtual eternity in sprint events.

“I don’t know,” I said. “Maybe I can swim faster than I did this morning.”

Arthur turned back to the front seat and rummaged around in his carrier bag. When he turned back to me again, he was holding a Rocky Road candy bar, full of marshmallows and milk chocolate.

“Eat this,” he said. “And you’ll win the race.”

Of course, I did.

There are so many sources, so many stories and far too much information to soundly bring together a coherent summation of a man who never forgot, never gave up and always cared so very deeply for many people. Towards the end of his life, during surgery to replace his knees, Arthur was beset with a stroke and heart attack but fought through his illness with his wife Joelyne to embark on more projects, such as a U.S. tour in 2004 from which he did not return.

But that was his nature, and if faced with a choice, there is no doubt which scenario Arthur would have picked as his last: sitting at home, inactive and old, or on the road, teaching, helping and encouraging the twenty-first century’s athletes. Someone who had to run twelve miles a day in Rome just to get to and from the athletic track where his runners were training isn’t the kind of dude who would want the rest of us to sit around and mull over how much we miss him or how we wish he were still here to tell us what to do.

He was alive for eighty-seven years and he did not put up with fools. The majority of his life was spent imparting his knowledge, and those who were paying attention know what he said. Lip-service is sacrilegious, because he had no time for pretty words and inaction. Believing in Arthur Lydiard is a religion not just of faith, but of works. And he sure proved that work, it does.

Beautifully written piece. You have an excellent writing style. It was a really interesting read. Thank you.